The Society of the Horseman's Word

The Society of the Horseman's Word was a fraternal secret society which operated from the eighteenth through to the twentieth century. Its members were drawn from those who worked with horses, including horse trainers, blacksmiths and ploughmen.

The Society originated in Scotland, and it is thought that the practises associated with the Society entered into East Anglia with Scottish prisoners of war from the Civil War era. With no possibly for defeated soldiers to be repatriated, many of them settled and sought work in our region. This theory gains credence from the fact that there is no evidence for the existence of the Society and its practices in East Anglia prior to the 17th century.

The Society was an informal forum for the passing on of useful knowledge, tips and ‘tricks of the trade’. But there is much continuing anecdotal evidence that in some areas, members of the Society engaged in magical and superstitious rituals believed to give horsemen an occult ability to control horses. Evidence of this is hard to find after such a long time, but rumours persist, as do vigorous denials (which, in themselves are interesting). But the Society also acted as a form of informal trade union or trade association, formed to protect its members and their rights.

Social aspects of the Society

The formation of the Society of the Horseman's Word in the late 18th-century coincided with the rise of the heavy horse as the primary draft animal for agricultural use. Before this, oxen were chiefly used. The period 1850-1950 was the ‘golden age’ of heavy horse power. The ability to break and control heavy horses became a much-valued skill. Men possessing these skills and knowledge were in high demand. This in turn lead to well-paid and high-status employment. It was in this context that the Society of the Horseman's Word was founded as an informal trades association, whose goal was to protect the interests of horsemen, and pass on their trade secrets. The Society also wanted to ensure that horsemen were properly trained, their wages were protected and that good practice was promoted.

As Ben Fernee says, ‘The ploughmen did not own the land, the horses, the harness, the ploughs or their homes. But they took control of the new technology, the horses, and ensured that only a brother of the Society of the Horseman’s Word might work them.’

Initiation Ceremony

The Horseman's Word initiation ceremony borrowed much from the 'Miller's Word', where bread and whisky were given as pseudo sacraments and the initiate was blindfolded. Like the Miller's Word, these ceremonies were often raucous and accompanied by pranks, ribaldry and much alcohol consumption. The members of The Society of the Horseman’s Word did however create their own passwords and oaths as well as rites of initiation.The initiation rituals of the Society also incorporated a number of quasi-magical features such as reading passages from the Bible backwards, masonic-style oaths, gestures, passwords and handshakes. Initiates were also believed by some to have practiced forms of folk magic or witchcraft. In East Anglia, horsemen with these powers were sometimes known as ‘horse witches’ or ‘horse-warlocks’ or ‘whisperers.’

It has been speculated that these initiation rituals were derived in part from the witches sabbat, or from published accounts of witches and their ceremonies. The initiate ( a young ploughboy or apprentice horseman) was presented with a token of invitation to attend an ‘initiation.’ This token was in the form of a twist of horse hair fashioned into a secret ‘horseman’s knot.’ This twist of horse hair would be slipped into the initate’s pocket, along with instructions as to when and where the ceremony was to take place (usually a secluded stable or barn at dead of night). The initiate was blindfolded and taken before the ‘master of ceremonies’ (often an older ploughman).

As in masonic ritual, there was an exchange of rehearsed questions and answers. In the case of the Horseman's Word (and the Miller's Word) this exchange was often a parody of the church catechism. After the initiation was completed the initiate was commanded to seal the pact and to ‘shake hands with the devil’ (usually a pole with a horse hoof attached to it, and covered in fur). The effect of such a solomn and eerie ceremony upon a young man can only be guessed at.

The 'Horseman's Word'

After the candidate had completed his initiation he was told a word which supposedly gave him magical power over horses.

As well as being a ‘secret society’. the ‘Horseman’s Word’ was actually a spoken word. This secret word (which varied from region to region) was said to have magical and mystical qualities. This would allow the possessor of the ‘word’ to control any horse by whispering it to the horse.

Apart from gaining knowledge of the secret ‘Word’, much practical advice about care and training of horses was also passed on to members of the society. This knowledge was kept secret in a way that preserved the mystique of their methods, and maintained the horsemen’s reputation as having unique (and even magical) power over horses.

Horseplay

Until they had undergone initiation and induction into the society, trainee horseman (and those who were not members of the Society) would often experiences difficulties when handling their horses. This was frequently a result of other horsemen playing tricks on them or tampering with their horses. Tin tacks under the horse's collar was a common trick (guaranteed to unsettle a horse and make it bad tempered. Burrs and thistles under the tail were also common causes of nuisence.

Jading a Horse

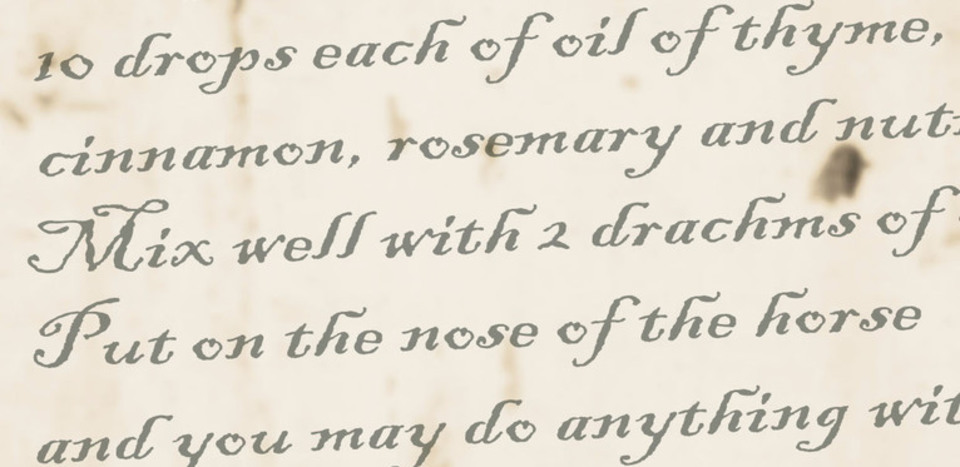

The use of jading’substances would also be used to make the horse difficult to work with. The hapless handler would be unaware of these tricks and games at their expense. Most of these techniques are based on the horse's sharp sense of smell. Foul substances placed in front of the horse or on the animal itself will cause it to refuse to move forward. This technique is known as jading and is still used by horse trainers today.

Drawing A horse

There were many attractively scented materials that were used to ‘draw’ a horse (to make a horse move forward and obey commands). These include peppermint, licorice, cinnamon and linseed. If the substance was in the form of an oil it could be wiped on the trainer's forehead. They would then stand in front of the animal and the smell would ‘draw’ it towards them.

Sometimes these substances were smeared inside the horse’s nostrils or mouth. This practice was often used in taming unruly horses. Other inviting titbits, such as sweets, would be kept in the horseman’s pocket in order to calm, attract, and subdue a difficult horse. Keeping these techniques secret, along with the myth that there was a word that only the horseman knew that gave them (and them alone) power over horses helped guarantee their reputation and prestige. The same type of logic and protection of trade secrets can be seen among modern magicians who keep their tricks secret and only share them with other members of their trade.

One critic of the Society, a ploughman who later became a grocer and published a book entitled Eleven Years at Farm Work; being a true tale of farm servant life (1879), claimed that ... 'Without betraying any secret, it may be said the real philosophy of the 'horseman's word', consists in the thorough, careful, and kind treatment of the animals, combined with a reasonable amount of knowledge of their anatomical and physiological structure.’

Historical studies

In the twentieth century, a number of scholars began to study the history and origins of the Society. The first of these, J.M. McPherson, published his findings and theories in his Primitive Beliefs in the North-East of Scotland (1929). He outlined the idea that the Society was a survival of an ancient pagan cult that had been persecuted in the witch trials in the Early Modern period.

Such ideas were supported by the folklorist Thomas Davidson in an article of his published on the subject of the Horseman's Word (1956), and then by George Ewart Evans, who purported the theory in four books of his published in the 1960s and 1970s. Nonetheless, around the same time that Evans was publishing his theory of a pagan survival, there were also researchers who had examined the origins of the Society and criticised the idea that it had ancient roots. In 1962, Hamish Henderson detailed how it had arisen in the eighteenth century, with his information being expanded upon by Ian Carter in his 1979 study of agricultural life in Scotland.

In 2009, The Society of Esoteric Endeavour published a compilation of nineteenth and early twentieth century texts about the Society in a volume entitled The Society of the Horseman's Word. Limited to an edition of one thousand copies, the first hundred copies contained an envelope inside within which was contained a piece of horse hair knotted in exactly the same manner as that which was originally used to invite prospective members into the Society.

Bibliography

Ankarloo, Bengt, and Stuart Clark. Witchcraft and Magic in Europe. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999.

Davidson, Thomas (1956). ‘The Horseman's Word’. Gwerin 2.

Evans, George Ewart (1966). The Pattern under the Plough. London: Faber. ISBN 978-0571243792.

___ (1979). Horse Power and Magic. London: Faber. ISBN 978-0571246649.

Carter, Ian (1979). Farm Life in Northeast Scotland 1840-1914. Edinburgh: John Donald.

Fernee, Ben, et al (2009). The Society of the Horseman's Word. Hinckley, Leicestershire: The Society of Esoteric Endeavour. ISBN 9780956371300.

Henderson, Hamish (June 1962). ‘A Slight Case of Devil Worship’. New Statesman and Nation.

___‘The Ballad, the Folk and the Oral Tradition’, in Cowan, Edward J. (ed.), The People's Past. Edinburgh: Polygon, 1980. ISBN 0-7486-6157-3

Hutton, Ronald (1999). The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198207441.

Kerr, Peter. Thistle Soup: A Ladleful of Scottish Life. Globe Pequot, 2004.

Maple, Eric (December 1960). ‘The Witches of Canewdon’. Folklore, Vol 71, No 4.

McHargue, Georgess (1981). The Horseman's Word: A Novel. Delacorte Press. ISBN 978-0385284721.

McPherson, J.M. (1929). Primitive Beliefs in the North-East of Scotland. London: Longman.

Neat, Timothy, The Horseman's Word. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-094-4

Pennick, Nigel 'Folk-Lore of East Anglia' (Spiritual Arts & Crafts Publishing 2006) ISBN 0-9551184-2-5

Porter, James. ‘The Folklore of Northern Scotland: Five Discourses on Cultural Representation.’ Folklore, Vol. 109 (1998): 1-14.

Samuel, Raphael (1981). People's History and Socialist Theory. London: Routledge.

Society Meetings. Folklore, Vol. 82, No. 1. (Spring, 1971): 88.